“I was compelled to pull out of the dive as my hatches flew apart.“

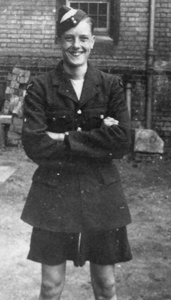

Dicky Bastow experienced four dramatic air incidents, including the one that killed him in May 1943.

His first actual combat was with 125 Squadron on 27 June 1942:

Dicky took off from RAF Fairwood Common on the Gower Peninsula just before 8 o’clock in the morning, flying a Mark II Beaufighter. He and his RO Clifford George were accompanying Squadron Leader Hughes, sweeping the Southern Irish coast for German intruder aircraft. Some two hours later they were vectored onto a ‘bandit’ 15 miles ahead of them and were lucky enough to get a visual sighting of it a long way ahead crossing cloud. They were at 15,000 ft and the German 3,000 ft lower, and they were pursuing with the sun behind them. The gap was quickly closed – 2 miles, a mile, half a mile – and then Hughes identified the bandit as a Ju88. Hughes attacked from 300 yards, then firing from 200 yards: ‘a long burst of at least 4 seconds’. The Ju88 was hit on port engine and fuselage, and a large piece broke off from its starboard side. In the meantime, return fire whizzed over the top of Hughes’ aircraft. Hughes fired again from his cannon, now from 150 yards, and finally at 50 yards with his machine guns. No return fire was coming now, and the German aircraft began a climbing turn to port, glycol pouring out of its starboard engine and it went into a diving turn to port, spiralling as it went.

At this point, Dicky Bastow closed in, putting his Beau into a dive and making another attack on the doomed Ju88 as it spiralled down. A large piece of its tailplane (or possibly fin or rudder) fell off it. The plane made one aileron turn, before bursting into flames and hitting the sea at high speed.

Sqn Ldr Hughes claimed one Ju88 destroyed, and Dicky Bastow wrote a corroborative statement:

“As S/Ldr broke off his attack, I saw the enemy aircraft turn away under him. I then dived on the E/A and gave it a 2 second burst from 250 yards. I was compelled to pull out of my dive as my hatches flew apart. I saw E/A dive into the sea in flames”.

Further combats to follow

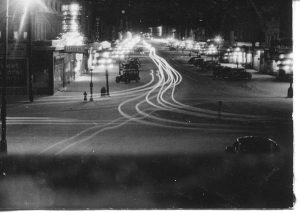

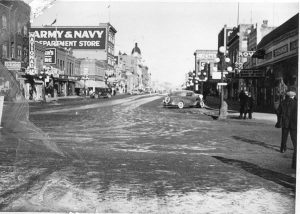

It was clear why the ‘powers that be’ had chosen the prairie sites to train pilots and other aircrew. The weather was excellent for flying (heavy snowfalls had finished by December) and the flat prairie landscape was of course free of obstacles. Furthermore, there was no blackout and so night-flying was easy to organise in terms of lighting, with plenty of runway lights and no problem in using powerful floodlights. The three of us stopped near one of the runways to watch a large machine equipped with giant rollers moving slowly along pressing down the snow. We nodded our approval; we had wondered how the loose snow was treated to allow an aircraft to take off safely.”

It was clear why the ‘powers that be’ had chosen the prairie sites to train pilots and other aircrew. The weather was excellent for flying (heavy snowfalls had finished by December) and the flat prairie landscape was of course free of obstacles. Furthermore, there was no blackout and so night-flying was easy to organise in terms of lighting, with plenty of runway lights and no problem in using powerful floodlights. The three of us stopped near one of the runways to watch a large machine equipped with giant rollers moving slowly along pressing down the snow. We nodded our approval; we had wondered how the loose snow was treated to allow an aircraft to take off safely.”